Data after Death

What happens to your data when you die? That's everything you’ve ever created or consumed online — the photos you took, music you heard, notes you wrote in the dead of the night.

Data may be hard to define, but it is a window into our lives. They are digital artifacts, living in perpetuity, exposing human personalities: what's on our mind, how it makes us feel, where it leads us to.

In the coming years, as our digital lives become more immersive, we will leave behind a trail of digital nuggets – little bits of ourselves scattered across the internet.

What happens to it all when we are gone?

Digital brains

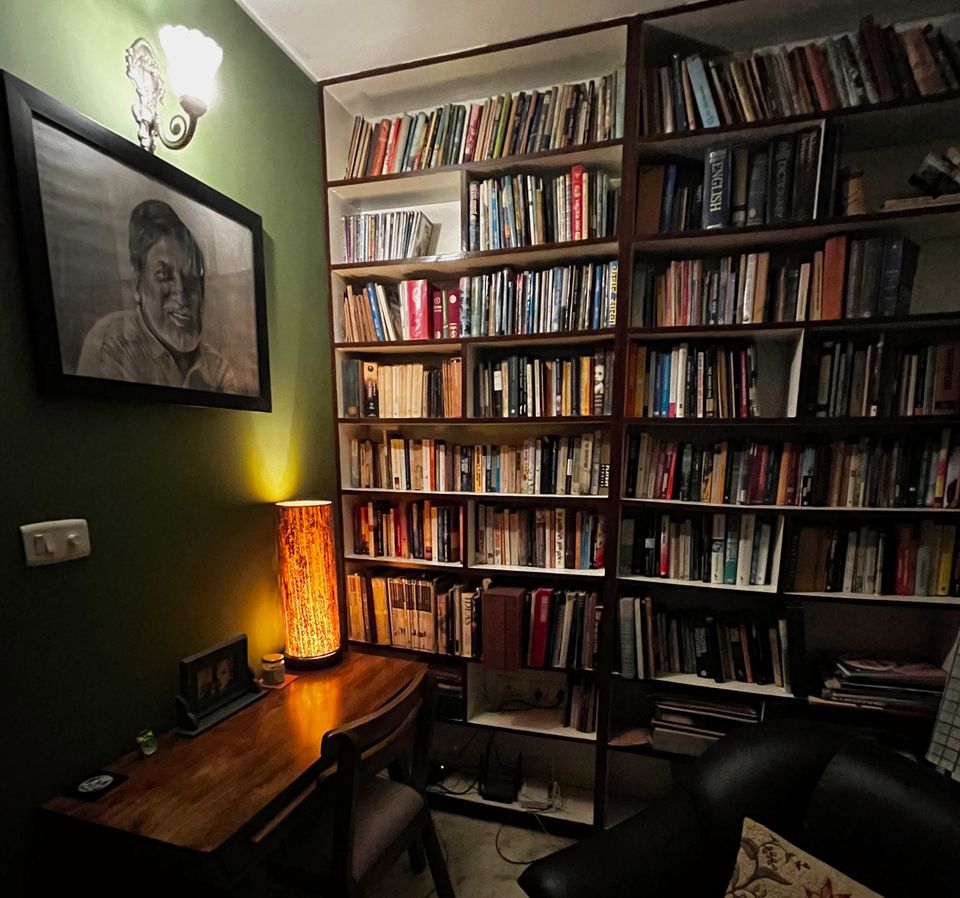

A few years after my father passed away, I stumbled upon a dusty leather pouch, nestled snugly beside his wire-rimmed glasses. It contained – amidst a sea of other memorabilia, including letters, photographs and concert stubs – a 500GB hard drive, Here was his ‘digital brain’ hiding in plain sight, containing his worldly wisdom.

In an essay for the New Yorker, Jill Lepore recounts finding a laptop that was bequeathed to her by a beloved friend Jane. In it, she found files named “transition notes” (book annotations), “future visions” (a two-year life plan), and the plainly titled “cancer stuff”. From Jill's experience and my own, it seems what one has lost of flesh and blood, one might rediscover in bits and bytes.

Like my father, I too am a disciplined chronicler of life experiences. I journal daily, take photos, bookmark essays, and curate playlists for different moods. My digital brain is well-nourished and all-encompassing, and with passing time, I expect to discover new tools to catalogue my life.

For this reason I think about who, in my absence, might benefit from a glimpse into my inner life, and how I could make it easier for them to access it.

Whose data is it anyway?

Computers today can store infinite amounts of data, at low cost and zero loss in quality. But nobody uses a 500GB hard disk anymore. Instead, we have come to rely on ‘digital intermediaries’ who help us store our memories on the cloud, and sort through massive databases of personal record.

There is a hidden cost to this. For one, our data will always be at the mercy of the platform’s whims. A cautionary tale emerges in the Hollywood Reporter, which laments the disappearance of certain movie titles from a streaming service for no good reason but the “caprices of the digital overlords”.

At a fundamental level, what data you can bestow depends on who owns that data. Unlike physical assets, multiple copies of the same digital asset can be possessed by different individuals simultaneously, each of whom can claim title.

Take for example a group photo taken on vacation. Does it belong to the person who clicked it, the one who uploaded it, the platform that hosts it, or to each one tagged in it? Data ownership is not obvious.

Data rights have also become fragmented with new proprietary formats and business models that prefer to license out content rather than let you own it. My father’s books, CDs and diaries were his to keep. But despite many years of legal training, I can’t say for sure that my e-books, music playlists, and social media posts are exclusively mine.

And even if the data is mine, what happens to it when I die?

Digital afterlife

In the brilliant documentary Transcendent Man, the futurist Ray Kurzweil makes a stunning claim: he will reincarnate his father by the year 2030 using AI and a lifetime’s worth of data.

This sounds like classic sci-fi, if not outright fantasy. Until you learn about the virtual world Somnium Space already markets a feature called “Live Forever”, which records your movements and conversations, then duplicates it as a digital avatar that moves and talks just like you, even after you have died.

Questions of reincarnation and consciousness are beyond the scope of this essay. But data is programmable. And that means, with the right tools, anyone can make data come ‘alive’.

The right to be remembered

Some days, I pull out my father’s hard drive and browse through his movie scripts and emails, wondering how he would have liked his ideas to survive. With the right tools, maybe an automated newsletter could go out to his friends: a snippet of his favourite dialogues, a song of the week, a photo for posterity...

But code isn’t enough. To realise this idea of a digital legacy, the law will have to step in. The Indian government seems to have recognised this. In the new data protection bill, users have a ‘right to nominate’ someone who will exercise their data rights in the event of death or incapacity.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t go far enough. What we need is a novel framework that gives individuals complete autonomy over their data. Not only to assign their data rights to another person, but also for example - the right to transfer their data to a secure platform, and a duty to ensure that the data is used in meaningful ways.

Some of these rights are already spelt out in modern technology laws through concepts like data erasure, portability and interoperability. But we need a comprehensive framework that brings together rights from multiple fields, like data governance, intellectual property, succession law and the concept of moral rights from copyright law.

For many years, experts have tried to define the contours of a ‘right to be forgotten’. For the sake of our loved ones, it is only fair that we also give them a right to be remembered.